The following article contains SPOILERS for True Detective.

If you’ve been browsing the internet anytime in the past few months you may have come across a series of theories by Jon Negroni connecting the films of Disney and Pixar into their own interlocking universes. For example, Boo from Monsters, Inc. eventually became the old witch inBrave, and the ship at the bottom of the sea in The Little Mermaid is the same ship that Elsa and Anna’s parents died on during the opening to Frozen (on their way to Rapunzel’s birthday celebration in Tangled, no less).

All of this begs the obvious question… why? Aren’t Disney movies enough as singular, self-contained stories? Do we have to seek out further meaning? Maybe the references and cameos are just that, and not the work of some god-like creative at Disney orchestrating the interaction of hundreds of characters and stories.

One could argue that these theories are harmless in it of themselves, merely helping to give internet sites a few extra clicks and their readers an amusing and thoughtful, but intellectually empty, waste of time. No one is harmed or that inconvenienced by their existence. But in a larger context, these theories are just the latest in a series of movies and TV shows that have caused viewers to search for meaning beyond the material, possibly at the expense of what these stories are actually trying to communicate.

Take for example HBO’s most recent hit show, True Detective. For those of you unfamiliar, True Detective is an anthology series that follows a different case and set of detectives each season, allowing the creative team to tell a singular story with a clear beginning, middle, and end over the course of eight episodes. It’s brilliant storytelling and another great addition to this so-called “Golden Age of Television” that we currently live in. Each week we were left guessing as to how things would progress, wondering how the creators were going to wrap up the different threads as we got down into the final episodes.

But as opposed to a show like Breaking Bad, the theories and speculation behind True Detective went deeper than what was going to happen to our favorite characters. You see, True Detective’s first season was steeped in the occult and satanic rituals. This was also a world where characters would spout off pieces of dialogue that delved deep into philosophy, theology, and spirituality. So when a victim’s diary made brief mention of The King in Yellow, a book of supernatural short stories published in 1895, the internet went crazy.

The ebook was available for free on Amazon shortly thereafter, and over the long week awaiting the next episode, and right up until the finale, everyone was making predictions and theories based on its contents. Week to week, ideas would fluctuate depending on what new information an episode would divulge. But one thing remained the same: we were in for a supernatural, perhaps even Lovecraftian, finale. I never got into this stuff, mostly because I don’t think a TV show should come with required reading, and thankfully neither did the series’ creator (but also because I realize 99% of the time I’m going to be wrong in my predictions and theories).

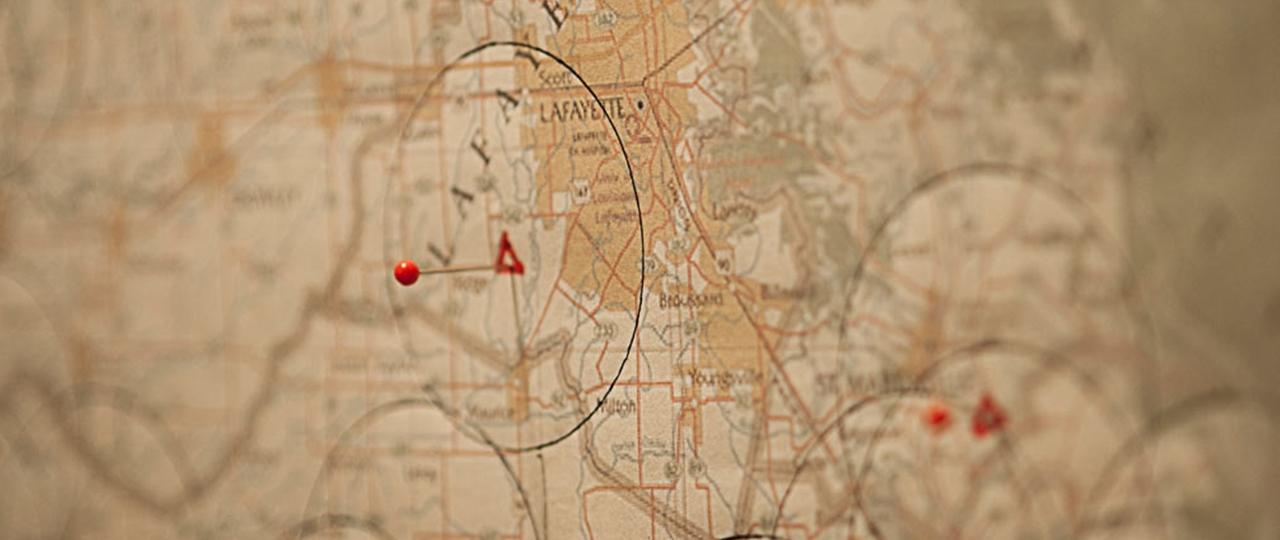

It’s interesting, now that True Detective is over, how much of the “mythology” had little or nothing to do with the final act. The show wasn’t building up to a supernatural revelation, but rather the conclusion of a character arc. The villain wasn’t some mystical king in yellow, but rather a backwoods redneck. Carcosa wasn’t a black hole or some other type of eternal abyss, it was a labyrinth of tunnels overgrown with thorns and branches (still scary though, if you ask me). And instead of affirming one of the lead’s nihilistic beliefs, the show ended on a note of hope. “Once there was only dark. If you ask me, the light’s winning.”

I won’t go so far as to say that all the theories were “wrong.” Everyone experiences art in their own way, and one of my favorite elements of this shared experience is reading and listening to different people’s opinions and theories. But there’s a difference between ideas that are in-line with the fictional world that’s been presented to us and ones that completely miss the forest for the trees.

For example, last year saw the release of Room 237, a documentary that is less about Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining and more about the conspiracies and theories that surround it. In it, you will find people who believe that Kubrick intended the film to act as a metaphor for the holocaust and Native American genocide, while others think it was his way to admitting to his involvement in the fake moon landing. There are even those who believe it to be a complex retelling of the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Yet, none of the film’s narrators ever once say that the movie is just about a frustrated middle-aged alcoholic who can’t face his own failures and instead decides to take his anger and frustration out on his wife and child (probably because this idea is way less fun to talk about than the Minotaur).

A lot of people were disappointed by the True Detective finale, but I for one loved it. The show was never about the supernatural, or even the overarching case for that matter. It was about these characters, their beliefs, their attitudes, and how they interacted off one another. Part of what made True Detective so great was its character work. In fact, the best episodes barely even involved the central mystery. Yet there was this insistence from the audience that somehow demons and monsters would manifest themselves in this realistic world, when in fact, if the show told us anything, it’s that man was the real monster. You only had to look at the series’ tagline, “Man is the cruelest animal,” to see that this was always the intention.

But perhaps this is just an inherent flaw of episodic or serialized storytelling. Loving a TV show is fundamentally tied up in loving something that is unfinished. When it comes to TV drama, we now seem to expect that half or more of the experience of the show involves looking forward to The Big Thing: whether that’s the “Red Wedding” in Game of Thrones or the finale to Breaking Bad.

It doesn’t help that ten years after Lost, networks are still making shows that spend half their time setting up long running mysteries instead of working on characters, essentially building their narrative foundation on nothing. Say what you will about Lost, but at least its otherworldly mystery was an integral part of that show’s basic premise. But this isn’t just the studios fault. It’s on us viewers as well.

Something in the television medium encourages us to look forward instead of backward, to use an episode as a clue towards a further mystery instead of as a work unto itself. Until its final episode, True Detective was an open book. Was it about Rust’s redemption or his corruption? Was Martin a good man or a psychopath? Is evil everywhere or does it reside in a thorny labyrinth? It was all fun to talk and read about, but it doesn’t really matter. The show chose the less fantastical, but perhaps better ending.

We all want to find some level of meaning in our stories, even if it means looking for meaning where there is none instead of looking at what the filmmakers have presented us. Did the top fall at the end of Inception or didn’t? It actually doesn’t matter. Whether it fell or not may change certain things about the story, but it doesn’t change the film’s theme of grief and reconciliation. It’s cases like this where the details seem to overwhelm the viewers to such an extent that they no longer understand the point of the story.

That isn’t to say everything should be cut and dry and easy to understand. I wouldn’t be able to write or even have discussing movies if they were so transparent. But we have to be careful where we look for meaning. To paraphrase True Detective, “You better start asking the right questions.”

Nick van Lieshout is an aspiring filmmaker and screenwriter. You can follow him on Twitter @Shout92.