This past weekend, Wes Anderson’s latest film The Grand Budapest Hotel opened up from four theaters across the US to 66. As of the time this article is being written, it has grossed over $4,779,000 and is rising. Anderson is one of the kings of independent film along with Steven Soderbergh and Kevin Smith, and his films always sport quirky characters in quaint, almost innocent settings despite the adult goings-on around them. But perhaps one of his most accessible works, and arguably his most popular film so far is his single foray into the world of animation: Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009).

Employing a nearly extinct form of animation, Anderson had decided to make a fully stop motion film using posable models. Even here, his unique style fits right in, as you can see hairs bristle as the characters (almost all anthropomorphic animals) move under the skillful guidance of puppeteers. But Anderson isn’t the only one to make a stop motion movie in recent history; Laika Entertainment released the animated films ParaNorman (2012) and Coraline (2009) within the past few years with The Boxtrolls set to be released later this year, and Aardman Entertainment has set a new benchmark with the Wallace and Gromit shorts, Chicken Run, and much more.

Chicken Run (2000)

From these, one would conclude that stop motion is still alive and kicking in the world of animation, and it’s true that we see a few of these films from year to year, despite the obvious popularity of fully computer animated films. But when was the last time you saw stop motion seriously used in a live-action movie? To be perfectly honest, the last one that comes readily to my mind was Sam Raimi’s Army of Darkness, which even there used it as kind of a novelty and to comedic effect. And that was release back in 1993! It’s no secret that stop-motion had been replaced long ago by the more easily manageable and manipulable computer generated animation. With CGI, you can create literally anything. Monsters, complex stunts, and entire environments are conjured up literally at our fingertips. As time progresses, it becomes more sophisticated and more difficult to see the computer generated seams. Back in the 90’s it was easy to spot a CG effect, now it can be difficult to tell where the real world ends and the animated world begins.

But is CGI always more convincing than stop motion? Are there places today when this “ancient” art form isn’t only acceptable, but should be preferred? The days of the immortal stop motion animator Ray Harryhausen died long before the man himself did (he passed away last year) and they won’t ever be back. This is understandable and I wouldn’t expect any less. Stop motion is clunky and almost mechanical-looking; you could never make a model of a living, breathing creature look believable today. But perhaps there’s a way to take the detriments of stop motion and turn them into strengths.

Some of Ray Harryhausen’s work in Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

For instance, let’s look at two of my favorite uses of stop motion when they’re used to be convincing. The first is James Cameron’s sci-fi noir classic The Terminator (1984). One of the most iconic shots in the entire movie is when Arnold Schwarzenegger’s humanoid robot sheds his skin and walks out of a burning wreck in full robot endoskeleton mode. This shot, and a few in the following scenes are completely done using stop motion, and they are terrifying. Rather than impeding the dark and realistic look of the movie, they enhance it. The limping, hell-bent terminator moves in motions that are somehow jerky while retaining fluidity. He jumps forward, joints rotating and limbs stretching out. He is, for all practical purposes, a real robot in a real situation. Jump forward to the 2009 sequel Terminator Salvation and there is a similar scene with a terminator losing its skin, and the effect just is not the same. Instead of seeing a demon from hell, we witness yet another computer-generated effect moving smoothly and effortlessly in its mad battle. This isn’t to say that CGI is bad in any way, but there’s a reason that the scene in the original stands out as a classic in horror, while this scene falls into obscurity. True, you can argue the merits and demerits of the films until judgement day, but we’re talking pure visual aesthetic here, and even bad movies can stand upon the strength of an indelible image.

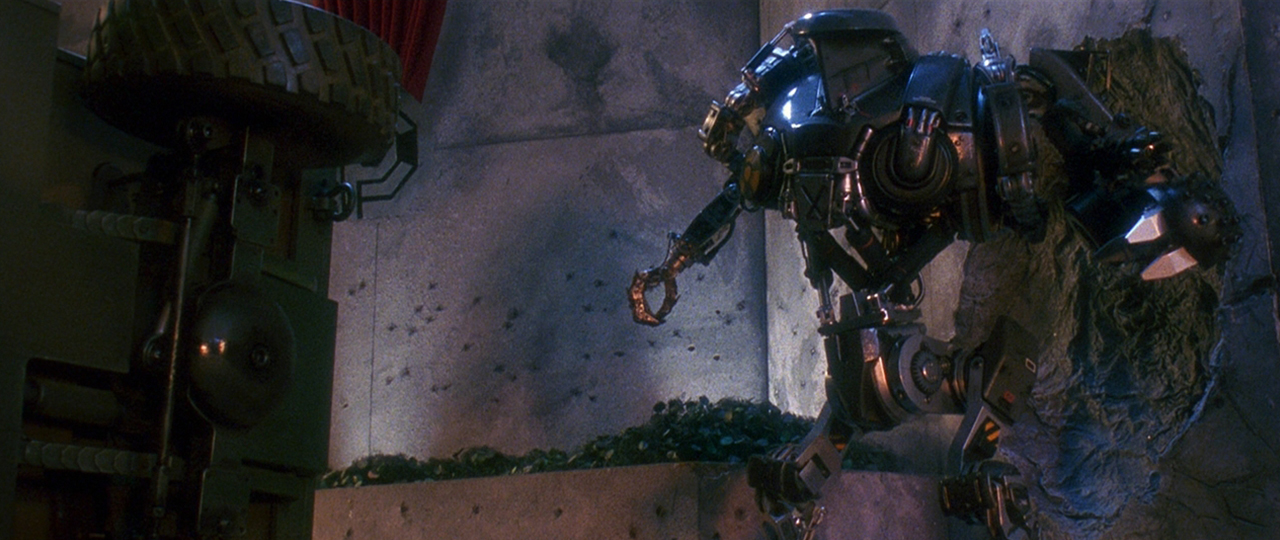

Similarly, the other instance where stop motion stands out in a place CGI would have failed is in the 1990 sequel Robocop 2. Here is an instance of a film that few people probably remember, and even fewer remember fondly. but towards the end there is a fight scene between the titular Robocop and his fully robotic nemesis. Despite the ridiculous nature of the movie and the scene, this stands out as one of the most well used instances of the animation medium. CGI was beginning to rising at the time, and starting to be more seriously considered as an alternative to other effects avenues, but here Irvin Kershner unapologetically decided to use full-on stop-motion to portray the two robotic characters battling, and it is mesmerizing. Using quick, bird-like movements this time, the main villain reveals rocket launchers and machine guns while it weaves around with mechanical accuracy. The stuttery movements combined with the presense of a physical object seals the effect, giving us something not only convincing to look at, but also visually fascinating.

Cain from Robocop 2 (1990)

Using these two examples, I would argue that there is a place for stop motion in today’s film world too. Obviously, computer generated imagery would be the smarter choice in the majority of films out there, but I think when you can put a physical object in front of the camera, it shows, and not at the seams. The robotic nature of stop motion can and should be utilized to its fullest advantage where applicable. Crafted with skill and perfected over time, it could be more realistic than any CG machine you build in the frame. Not only that, but it’s different enough that nobody expects to see it now. It’s so old that it’s new. It’s perfectly understandable that this is a lost practice, but I think there’s room for another Ray Harryhausen in the world eventually. Perhaps one day, some kid will watch Earth Vs the Flying Saucers, Jason and the Argonauts, or even John Carpenter’s The Thing and think, “How did they do that?”, and even more importantly, “How can I do that?”.

In any case, we still have the classics to revisit, even if its for novelty’s sake. Maybe it’s enough that they remain a piece of history to be shown and cherished. And maybe it’s best that we leave the future to pave itself with something new rather than look to the past for outdated guidance. Maybe.

Joe Campbell is a short film director and movie enthusiast. You can follow him on Twitter @joemicampbell or on Google+.